Introduction | Main trends | Informal sector | Access to finance | Electricity | Tax administration | Corruption | Workforce skills | Management practices and innovation | Conclusion

Governments across the transition region are continuing to improve the local business environment in an attempt to unleash the full productive capacity of the private sector. This report summarises feedback from the managers of firms in 29 transition countries about what they regard as the main improvements – and the remaining challenges – in the business environment that they experience on a daily basis. Across the board, managers reported that they were most constrained by (i) unfair competition from the informal sector, (ii) limited access to credit and (iii) expensive or unreliable electricity supply.

In the wake of the global financial crisis, governments in the transition region are continuing to search for ways to resuscitate economic growth. One course of action is to create a more conducive business environment, which can boost growth by establishing competitive and fair conditions for all businesses.

This report summarises the key results of the fifth round of the Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Survey (BEEPS V), which was conducted by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and the World Bank Group in 29 countries. The survey was conducted in Russia in 2011-12 and in 2013-14 in all other countries. Senior managers were interviewed at more than 15,500 randomly selected firms. Those firms – all of which had at least five employees – spanned 29 of the EBRD’s countries of operations. Chart 1 shows the geographical coverage of the BEEPS V survey.

Managers were asked for their views on topics such as infrastructure, competition, sales and supplies, labour, innovation, land and permits, crime, finance, and relations between business and government. They were also asked about the management practices in their firms.

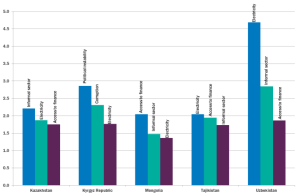

In BEEPS V, the top three obstacles identified by firms in the transition region were (i) competitors’ practices in the informal sector, (ii) access to finance and (iii) electricity. In BEEPS IV, which was conducted in 2008-09, the same three obstacles made up the top three, with access to finance and competitors’ practices in the informal sector switching places. Chart 2 shows the top three obstacles in each country according to BEEPS V.

It is important to note that the analysis is based on constraints as perceived by each firm. As such, it can only indicate policy priorities and cannot be used to rank countries by the quality of their business environments.i

CEB countries

SEE and Turkey

CA

Source: BEEPS V and author’s calculations.

Note: BEEPS V was conducted in 2013-14 (2011-12 in Russia) Estimated for a hypothetical “average” firm. Higher values correspond to a weaker business environment.

Informal sector

Firms in almost a third of all countries considered competitors’ practices in the informal sector to be the biggest obstacle. There were just nine countries where the informal sector was not one of the top three concerns, and it was in the top eight in all countries. This issue transcends regional boundaries, being the main constraint from Azerbaijan to the Slovak Republic. The shadow economy is more than just unregistered firms. Registered firms often under-report their income, hide employees or fail to declare wages (termed “envelope wages”) to avoid taxes or the need for documentation. Such activities are widespread in businesses that deal largely in cash, such as small shops, bars and taxi companies, as well as firms in the construction, agriculture and household services sectors.

Access to finance

Access to finance was also regarded as a major constraint. It was the top constraint in Armenia, Croatia, Russia and Mongolia, and it was among the top three in another 14 transition countries. Given that BEEPS V was conducted at a time when many banking sectors were still recovering from the severe effects of the global financial crisis, this is hardly surprising. In virtually all countries, the percentage of firms with a loan or a line of credit fell by comparison with BEEPS IV. Limited access to finance is a particularly acute problem for firms younger than five years. This was driven by a substantial decline in demand for credit, with only a small reduction being seen in the supply of credit.

Electricity

Electricity issues were the main obstacle in Albania, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, and they were among the top three in a further 12 transition countries. The underlying reasons differed across countries. In Central Asia, it was mostly to do with unreliable electricity supply, which was characterised by frequent and costly power outages. In central Europe and the Baltic states (CEB), on the other hand, it stemmed from high electricity prices.

Not all types of firm complain about the same aspects of the business environment. The retail sector, for instance, is typically more exposed to the shadow economy than the manufacturing sector, especially when it comes to smaller firms. Moreover, young firms play a particularly important role in creating jobs, so it is important to understand which types of obstacle they consider to be the most problematic.

In BEEPS V, young firms were most constrained by limited access to finance, rather than competitors’ practices in the informal sector. This was the case in all regions, with the exception of south-eastern Europe (SEE) and Turkey. In the presence of relatively strict collateral requirements, and stringent lending procedures more generally, young firms with a limited track record find it particularly difficult to demonstrate their creditworthiness and obtain loans in order to continue growing. While policy-makers have implemented many programmes focusing on SMEs’ access to finance, hardly any of those programmes specifically support young firms.

In the CEB region, where corruption tends to be less prevalent, onerous tax systems were a major obstacle for young firms. This often related to the time that it took to fulfil tax obligations.

Large firms, on the other hand, complained most about electricity – particularly firms in Central Asia and Russia. In CEB countries, which have fairly strict labour regulations (particularly for permanent employees), those regulations were the second biggest obstacle. Many of these countries were hit hard by the global financial crisis, and the fact that those strict laws prevented firms from adjusting the number of workers in line with shrinking demand may explain this result.

Competitors’ practices in the informal sector were the top constraint for retail-sector firms in transition countries, while manufacturing firms complained most about limited access to finance.

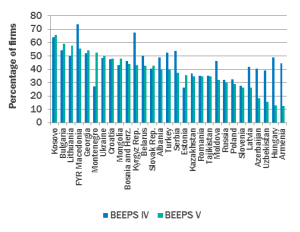

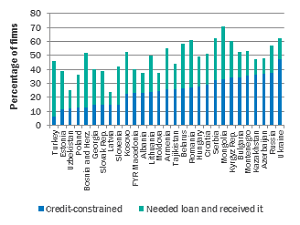

Competitors’ practices in the informal sector were the main obstacle reported by firms in BEEPS V. Almost 40 per cent of all firms mentioned that they faced competition from unregistered firms or other informal-sector activities, with that percentage ranging from 12.8 per cent in Armenia to almost two-thirds in Kosovo (see Chart 3). In several countries, mostly in Central Asia, that percentage declined substantially relative to BEEPS IV. In the SEE region, it fell from almost three-quarters to 55 per cent in FYR Macedonia, but it almost doubled in Montenegro, where it stood at 52.4 per cent.

Source: BEEPS IV and V and author’s calculations.

Note: BEEPS IV was conducted in 2008-09. BEEPS V was conducted in 2013-14 (2011-12 in Russia).

Although unregistered firms can still be found in transition countries, these days the motivation for engaging in informal-sector activities stems mainly from registered firms’ desire to evade tax by under-reporting income or not fully declaring employee numbers or wages. In the last few years, several transition countries have made it much easier to officially establish a business by setting up one-stop shops and reducing registration costs. However, it may take a while to convince unregistered firms to register and reduce the informal-sector practices used by registered firms.

The shadow economy can make entrepreneurship less profitable, hamper investment (by restricting access to credit), undermine broader private-sector development and reduce social protection, thereby stifling economic growth and prosperity. On the other hand, the shadow economy can also provide an outlet for economic activity (mainly in the form of small and medium-sized firms) that is unable to flourish in the face of excessive barriers to enterprise in the formal sector.

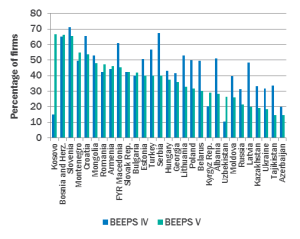

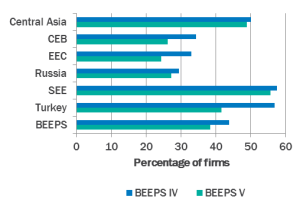

Chart 4 shows the percentage of firms that reported having a loan or a line of credit in BEEPS V, comparing those figures with the data for BEEPS IV. That percentage fell in most transition countries. In Albania, Latvia, Lithuania and Serbia, it declined by more than 20 percentage points. The largest average declines were recorded in the CEB region and Turkey – the transition countries that have the strongest ties to the global economy. Consequently, they were also the most strongly affected by the global economic crisis.

Source: BEEPS IV and V and author’s calculations.

Note: BEEPS IV was conducted in 2008-09. BEEPS V was conducted in 2013-14 (2011-12 in Russia).

The SEE region includes both countries that saw large increases in the percentage of firms with a loan (such as Kosovo and Montenegro) and countries with large declines (such as Albania and Serbia). There are several reasons for these differences. Firms in Kosovo used to rely more on friends and family for funds, being supported by significant inflows of remittances. However, when the global financial crisis struck and remittances declined, they turned more towards banks. Moreover, Kosovo declared its independence from Serbia in February 2008 and several banks have entered the market since then, competing for market share and improving the availability of credit in the process. Albania, FYR Macedonia and Serbia, on the other hand, have had high levels of non-performing loans for a long time, and lending activity has declined owing to deleveraging by Western (particularly Italian and Slovenian) banks. It has also been affected by the problems of Greek banks, which have a significant presence in all of those countries.

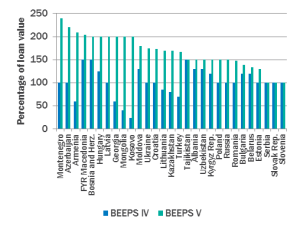

Chart 5 shows that the median collateral required for financing has increased in virtually all countries as a percentage of loan value. This has made it more difficult for firms, in particular the younger ones, to access bank credit.

Source: BEEPS IV and V and author’s calculations.

Note: BEEPS IV was conducted in 2008-09. BEEPS V was conducted in 2013-14 (2011-12 in Russia).

The percentage of firms that had applied for a loan also decreased substantially, declining by almost a third compared with BEEPS IV (falling from 38.1 per cent to 24.7 per cent). This suggests that part of the deleveraging process across the transition region is demand-driven. In the aftermath of the crisis, many firms have revised their investment plans downwards or abandoned them altogether, so they no longer have any need for a bank loan. A clear and unambiguous measure of whether firms are credit-constrained can be created by combining firms’ answers to various BEEPS questions. Credit-constrained firms are defined here as those that need credit but have either decided not to apply for a loan or were rejected when they applied.

Almost half of all firms surveyed in BEEPS V reported needing a bank loan. A total of 51.3 per cent of them turned out to be credit-constrained. In BEEPS IV, 60.0 per cent of surveyed firms needed a bank loan, with 46.5 per cent of them being credit-constrained. Taken together, this indicates that there was a fairly substantial decline in demand for credit and only a small reduction in supply.

There was, however, substantial variation across countries (see Chart 6). Demand for credit decreased everywhere, except Hungary, Kosovo, Romania and Ukraine. In contrast, the percentage of credit-constrained firms increased in almost two-thirds of countries relative to BEEPS IV. Particularly strong declines in access to credit were observed in Albania, Slovenia, Ukraine and Russia (all of which saw increases of more than 20 percentage points in the percentage of credit-constrained firms), followed by Croatia and Lithuania. At the other end of the spectrum were countries where the percentage of credit-constrained firms decreased relative to BEEPS IV. The largest decline was seen in Kosovo, where that percentage fell from 73.9 per cent to 43.3 per cent owing to the entry of new banks following the declaration of independence from Serbia in February 2008.

Source: BEEPS V and author’s calculations.

Note: BEEPS V was conducted in 2013-14 (2011-12 in Russia).

Limited access to credit may not only constrain firm growth in the short term, but may also have longer-term negative effects. BEEPS results show that where banks ease credit constraints, firms tend to innovate more by introducing products and processes that are new to their local and national markets.

Issues related to electricity remained the third largest obstacle to firms in BEEPS V. However, looking at the transition region as a whole, some improvements have been made since BEEPS IV. The average time that it takes to be connected to electricity fell from 49.5 days in BEEPS IV to 36.3 days in BEEPS V, while 38.4 per cent of firms reported experiencing power outages in BEEPS V, compared with 43.7 per cent in BEEPS IV. In addition, the average number of power outages decreased from 6.4 to 5.2 per month, and they lasted almost an hour less on average (3.7 hours, compared with 4.6 hours in the previous round). That being said, the percentage of firms reporting that informal gifts and payments had been expected or requested in return for being connected increased from 10.7 per cent in BEEPS IV to 12.1 per cent in BEEPS V.

There remain, of course, significant differences across countries and regions. In Turkey and several CEB countries, industrial electricity prices increased before and/or during the period of the survey, leading companies to complain about electricity issues, even though the time it took to be connected was relatively short, the percentage of firms reporting power outages was low and the percentage of annual revenue that was lost owing to power outages was lower than in some other regions. In Central Asia, on the other hand, firms still have to deal with an unreliable electricity supply, frequent power outages and corruption when it comes to being connected.

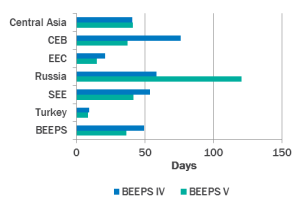

Firms in Turkey had to wait an average of just eight days or so to be connected to electricity. Meanwhile, firms in the CEB region saw average waiting times decline the most (from 76 to 37 days) between the two BEEPS rounds (see Chart 7). There are several explanations for this. First, these countries joined the EU in May 2004, adopting the first and second EU electricity liberalisation directives. They were therefore required to take a minimum number of steps towards the liberalisation of their national markets by certain key dates. Second, around 2007 EU member states began to exchange best practices in terms of the procedures required to get connected to electricity, and progress was made following the establishment of the Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators in 2010. Third, there were improvements in the resources and abilities of most national energy regulators during this period. Estonian firms, in particular, saw a vast improvement in the time taken to get connected – from over 200 days in BEEPS IV to just 15 days in BEEPS V. This reflects that 35 per cent of the electricity market was liberalised in 2009 (at which point customers using at least 2GWh/year could choose their electricity supplier) with full liberalisation following in 2013.

Source: BEEPS IV and V and author’s calculations.

Note: BEEPS IV was conducted in 2008-09. BEEPS V was conducted in 2013-14 (2011-12 in Russia).

In Russia, however, the average waiting time doubled, from 58.6 days to over 120 days, giving officials ample opportunity to seek informal payments. Indeed, 11.4 per cent of Russian firms reported that an informal payment was expected or requested when they applied to be connected – second only to Central Asia (see Chart 8). According to the World Bank’s Doing Business report for 2014, Russia has since made it easier to get connected, setting standard connection tariffs and eliminating many of the procedures that were previously required, so an improvement can be expected in the next BEEPS survey.

Source: BEEPS IV and V and author’s calculations.

Note: BEEPS IV was conducted in 2008-09. BEEPS V was conducted in 2013-14 (2011-12 in Russia).

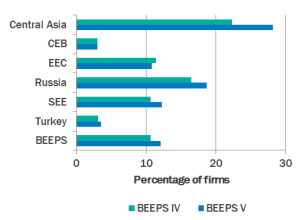

Compared with BEEPS IV, the percentage of firms reporting informal payments were expected or requested increased most strongly in Central Asia – particularly in Mongolia, the Kyrgyz Republic and Kazakhstan.

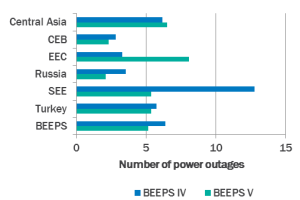

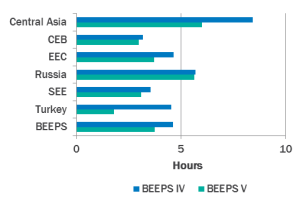

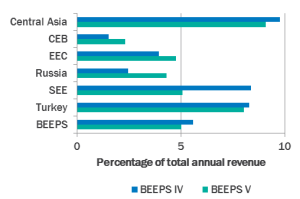

Firms in Central Asia also had to deal with more than their fair share of power outages, with almost half of them experiencing outages. While power outages were, on average, experienced by a larger percentage of firms in the SEE region (see Chart 9), Central Asia came out on top – followed by Turkey and the SEE region – in terms of the number of power outages in a typical month, their duration and the losses resulting from them (see Charts 10 to 12).

Source: BEEPS IV and V and author’s calculations.

Note: BEEPS IV was conducted in 2008-09. BEEPS V was conducted in 2013-14 (2011-12 in Russia).

Source: BEEPS IV and V and author’s calculations.

Note: BEEPS IV was conducted in 2008-09. BEEPS V was conducted in 2013-14 (2011-12 in Russia).

Source: BEEPS IV and V and author’s calculations.

Note: BEEPS IV was conducted in 2008-09. BEEPS V was conducted in 2013-14 (2011-12 in Russia).

Source: BEEPS IV and V and author’s calculations.

Note: BEEPS IV was conducted in 2008-09. BEEPS V was conducted in 2013-14 (2011-12 in Russia).

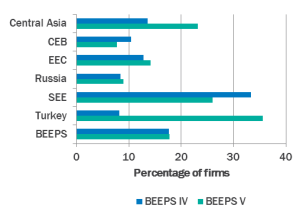

Nevertheless, several SEE countries (such as Albania) have seen improvements in the reliability of their electricity supply, partly owing to increased precipitation. Most Central Asian countries have to deal with transmission bottlenecks, as well as ageing power plants. While they are addressing those problems to the best of their abilities, at least some of the improvements seen since the last BEEPS survey can be attributed to a higher percentage of firms (23.2 per cent, up from 13.6 per cent) taking matters into their own hands by owning or sharing an electricity generator (see Chart 13). In Turkey, the substantial increase in the percentage of firms that own or share a generator can partly be explained by the fact that they are able to sell surplus electricity from renewable generators to power distribution companies since December 2010.

Source: BEEPS IV and V and author’s calculations.

Note: BEEPS IV was conducted in 2008-09. BEEPS V was conducted in 2013-14 (2011-12 in Russia).

Tax administration was among the top three obstacles in 7 of the 29 countries in BEEPS V, as it had been in BEEPS IV. It remained the top obstacle in Romania, it became the main constraint in Hungary and Poland, and it was considered to be the third largest obstacle overall by firms in the CEB region.

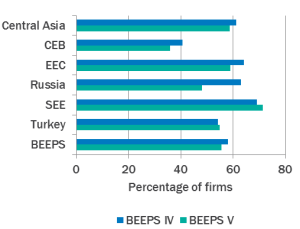

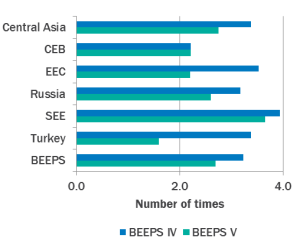

This does not appear to be caused by the carrying out or frequency of tax inspections, or the fact that informal payments were expected or requested during inspections or meetings with tax officials – although increases have been observed for some of these things in certain countries. The percentage of firms that had been visited or inspected by tax officials remained broadly unchanged overall – at over 55 per cent – and declined in Central Asia, the CEB region, eastern Europe and the Caucasus (EEC), and Russia (see Chart 14). The number of times that firms had been inspected by tax officials or required to meet them declined everywhere bar the CEB region (where it remained broadly unchanged), averaging just over two visits or meetings per year (see Chart 15). Several countries had also made it easier to pay tax by introducing electronic filing and payment systems or reducing the number of payments.ii All of these measures reduced tax officials’ opportunities to seek informal payments. Indeed, with the exception of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Kosovo, the Kyrgyz Republic, Lithuania, Montenegro and Ukraine, the percentage of firms reporting that informal payments were expected or requested either decreased or remained broadly unchanged relative to BEEPS IV.

Source: BEEPS IV and V and author’s calculations.

Note: BEEPS IV was conducted in 2008-09. BEEPS V was conducted in 2013-14 (2011-12 in Russia).

Source: BEEPS IV and V and author’s calculations.

Note: BEEPS IV was conducted in 2008-09. BEEPS V was conducted in 2013-14 (2011-12 in Russia).

It is more likely that the perceived severity of tax administration can be explained by “crisis taxes” and the unpredictability of countries’ tax regimes. Hungary, for example, introduced a sector-specific surtax in 2010 (abolished in 2013), which applied to the energy, retail and telecommunications sectors, while Poland increased social security contributions. Serbia increased many tax rates as part of the fiscal consolidation package that it adopted in 2012. The way that taxes are calculated and paid offers an alternative explanation. In most countries, firms are required to pay tax in advance on the basis of the tax paid or profits made in the previous year. However, this did not take account of the fall in revenues owing to the global financial crisis.

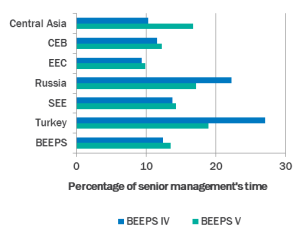

Furthermore, the percentage of senior managers’ time that is spent dealing with requirements imposed by government regulations – such as taxes, customs, labour regulations, licensing and registration (including dealing with officials and completing forms) – increased by an average of around one percentage point, rising from 12.4 per cent in BEEPS IV to 13.5 per cent in BEEPS V (see Chart 16). The largest increases were recorded in Central Asia, while Russian and Turkish firms reported significant decreases.

Source: BEEPS IV and V and author’s calculations.

Note: BEEPS IV was conducted in 2008-09. BEEPS V was conducted in 2013-14 (2011-12 in Russia).

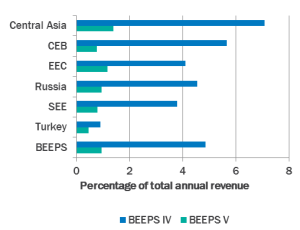

Corruption remains one of the main obstacles in transition countries, particularly for young firms. There is scope for corruption in any interaction that requires contact between firms and service providers or government officials. As discussed earlier, there was a slight increase in the share of firms reporting that informal payments were expected or requested when applying to be connected to electricity, but there was a decline in the share of firms reporting that informal payments were expected or requested by tax officials. Likewise, there was a decrease in the share of firms reporting that informal payments were expected or requested in order to obtain an import licence or an operating licence. There was an even larger decline in informal payments made to public officials to “get things done” with regard to customs, taxes, licences, regulations, services and the like, as well as an increase in the percentage of firms that reported never making such payments. In BEEPS V, firms reported that they paid out just under 1 per cent of their annual revenue for this purpose. In BEEPS IV, it was almost 5 per cent (see Chart 17). These positive developments can, to some extent, be explained by the introduction of electronic filing and payment systems in several countries, which reduces the amount of interaction between firms and officials and thereby reduces the opportunity and temptation to seek informal payments.

Source: BEEPS IV and V and author’s calculations.

Note: BEEPS IV was conducted in 2008-09. BEEPS V was conducted in 2013-14 (2011-12 in Russia).

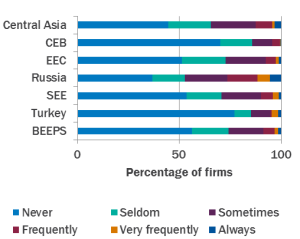

The size of informal payments made to public officials to “get things done” decreased in all regions and in all countries. However, this type of corruption remained widespread in Russia and Central Asia, where less than 45 per cent of enterprises reported that they never made such payments (see Chart 18). Furthermore, in several countries the percentage of firms that made such payments at least occasionally increased relative to BEEPS IV – by more than 10 percentage points in Russia, Armenia and Lithuania.

Source: BEEPS IV and V and author’s calculations.

Note: BEEPS IV was conducted in 2008-09. BEEPS V was conducted in 2013-14 (2011-12 in Russia).

Workforce skills were among the top three obstacles in 11 of the 29 countries in BEEPS IV. In BEEPS V, however, this was the case in only 5 countries. The reason for this positive trend is not so much an improvement in education and training in the intervening period, but rather the global financial crisis, which affected the availability of skilled workers through three different channels: (i) reduced demand for skilled workers on the part of firms, which abandoned expansion plans or even shrunk; (ii) higher unemployment owing to firms laying off workers or going out of business, resulting in an increased supply of skilled workers; and (iii) fewer skilled workers moving abroad and/or more returning home, owing to economic conditions being worse abroad and/or better at home. Reliable data on immigration and emigration are hard to find, but the available information is at least indicative of general trends.

A case in point is Poland, where workforce skills were the second largest obstacle in BEEPS IV, a result of a significant number of Poles leaving the country after 2004. The Polish economy performed relatively well during the global financial crisis, and many of those Poles returned. According to Eurostat data, the number of people moving to Poland was more than ten times the pre-crisis level during that period. As a result, workforce skills fell to eighth place in the list of obstacles in BEEPS V.

Romania’s experience was similar – although not quite as dramatic – with workforce skills falling from third to fifth place. In 2010, 3 million Romanians (14.8% of the population) were estimated to be working abroad – mostly in Italy and Spain, which were hit hard by the crisis. This led to a significant reduction in the number of Romanians emigrating, as well as more Romanians returning home.

Workforce skills remained among the top three obstacles in the Baltic countries, Belarus and Moldova, which have experienced high levels of emigration in recent years. In the case of the Baltic countries, emigration – primarily to EU member states – increased after they joined the EU in 2004. In all of them, the number of people leaving dropped slightly in 2007. In Latvia and Lithuania, emigration then increased again as a result of the global financial crisis, which hit both countries hard. While emigration has decreased in recent years, it remains above pre-crisis levels. In Estonia, on the other hand, the number of people emigrating has continued to increase since 2007.

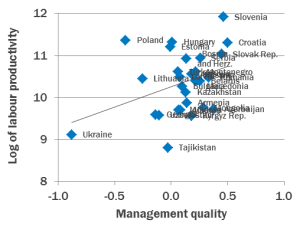

There are other ways of improving firms’ productivity, besides improving the external business environment. Firms’ managers can make better use of excess capacity (if they have any), they can cut costs (shedding labour where necessary), and they can improve the way they manage their businesses. That is to say, firms themselves can improve how they handle production-related problems, monitor their production and set targets, as well as the way they deal with poor performers and reward high achievers. There is a strong correlation between the quality of management practices and firms’ productivity (see Chart 19). In every country, there are firms with both good and bad management practices. A lack of managerial skills is one explanation for the low productivity of state-owned or state-controlled firms.

Source: BEEPS V and author’s calculations.

Note: BEEPS V was conducted in 2013-14 (2011-12 in Russia).

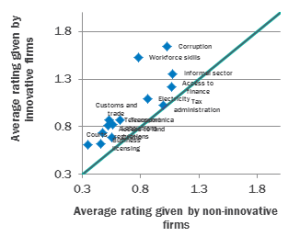

However, the most common and the most important driver of change within firms (particularly in advanced industrialised countries) is innovation, and the results of BEEPS V show that firms that have introduced a new product or process regard all aspects of their business environment as a greater constraint on their operations than firms that have not done so (see Chart 20). The differences between the views of innovative and non-innovative firms are especially large when it comes to workforce skills, corruption, and customs and trade regulations. Corruption is among the main constraints for all firms, and it is an even greater constraint for innovative firms. In contrast, customs and trade regulations are not major concerns at the level of the economy as a whole, partly because only a relatively small number of firms import production inputs or export their products directly. However, customs and trade regulations specifically affect innovative firms, as the introduction of new products and processes is often dependent on imported inputs and the ability to tap export markets.

Source: BEEPS V and author’s calculations.

Note: BEEPS V was conducted in 2013-14 (2011-12 in Russia). Innovative firms are defined as firms that introduced new products or processes in the last three years.

Interviews with the managers of more than 15,500 firms across the transition region reveal that there has been only limited progress in regards to the main business environment constraints highlighted in the 2008-09 survey. Firms continue to complain first and foremost about informal competition from the shadow economy; their inability to access credit at reasonable terms; and problems related to accessing reliable and affordable electricity.

Since the 2008-09 round, firms have been considerably less constrained by the court system, business licensing and permits, and workforce skills. Improvements in courts and red tape were mainly the result of measures taken by various governments. FYR Macedonia, for example, revised most of its corporate governance in line with the European Union and international standards and equipped courts with electronic case management systems, which made the enforcement of contracts easier. Inadequate workforce skills, on the other hand, became a less severe obstacle due to increased return migration into the transition region in the wake of the global financial crisis.

(i) Respondents’ answers may reflect differences in their “propensity to complain” – that is to say, differences in firms’ sensitivity to constraints on their business – rather than actual differences in those constraints. For example, growing firms may regard workforce skills as more of an obstacle than shrinking firms, even if they are both in the same sector and location. In order to address this difficulty, this analysis uses the perceived severity of constraints to measure the quality of the various components of the business environment and controls for characteristics of individual firms (including size, age, industry and export activity), as well as characteristics of the individual manager who responded to the survey (such as gender, length of service and position within the firm).

(ii) According to Doing Business, Romanian firms have seen the average number of payments per year decrease from over 100 in 2008-09 to 39 in 2012-13 and 14 in 2013-14. Serbian firms still faced a total of 67 payments per year in 2013-14 (the highest figure in Europe).